7 Years On: Reflecting on Indigenous Law since TWN’s TMX Impact Assessment

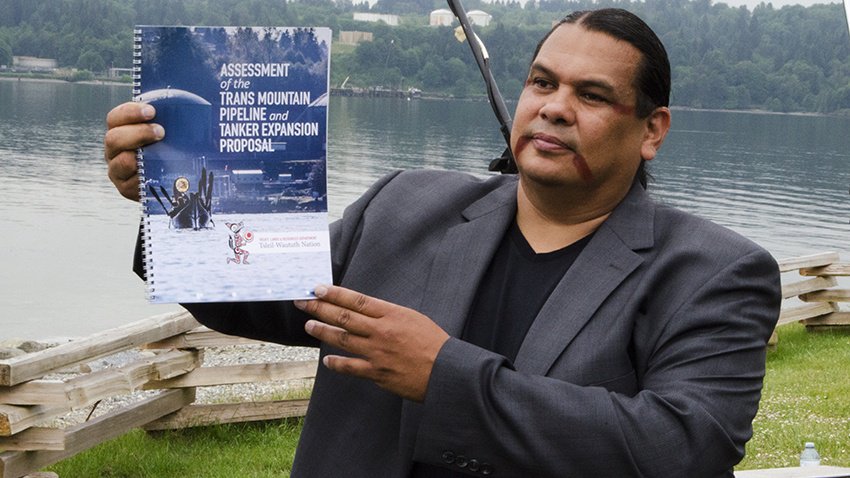

On May 26, 2015, Tsleil-Waututh Nation launched our independent assessment of the Trans Mountain pipeline and tanker expansion (TMX), grounded in Tsleil-Waututh’s unextinguished law and contemporary policy. The assessment consisted of scientific analyses by world-leading experts on issues such as oil spill risk, as well as traditional TWN knowledge about Burrard Inlet, in order to evaluate the impacts the proposed pipeline and tanker expansion would pose to TWN and its lands and waters, including the Nation’s rights, title, and interests.

The Assessment’s Continued Relevancy

Tsleil-Waututh’s Assessment of TMX continues to be celebrated and upheld seven years on. Just last month, former chief Leah George-Wilson was a featured speaker discussing TWN’s assessment at an event organized by Osgoode Law during the International Association of Impact Assessment conference. Why do we continue to celebrate this document that is now 7 years old, for a project that has since been approved by Canada despite TWN’s informed decision to withhold consent?

The assessment continues to be a leading example of how a First Nation can apply its own law in dialogue with Canadian law, how a First Nation such as TWN expresses its jurisdiction, and how Indigenous-led assessments can present robust analyses that help us understand the impacts of a project beyond the limiting scope of traditional provincial or federal environmental assessments.

TWN’s own assessment, rather than simply duplicating work that agencies such as the National Energy Board (NEB) or environmental assessment regimes may carry out, reviewed the project from an inherently different perspective, filling in gaps and asking questions that the province and Canada are simply unable to. While elements of TWN’s assessment may be familiar—overviews of the biophysical impacts within the study area, for example— other sections are inherently unique to Indigenous perspectives, such as the impact the project has on TWN members’ rights to practice their culture, including their ability to conduct ceremony, or safely harvest shellfish. Further, the risk assessments carried out in the assessment are considered through the lens of Tsleil-Waututh law, including the obligation for Tsleil-Waututh to protect its lands, waters, and air so that future generations can thrive.

Tsleil-Waututh means “People of the Inlet.” Burrard Inlet, or səlilwətaɬ, is the location of our creation stories. Tsleil-Waututh’s deep understanding of the lands and waters in and around Burrard Inlet span thousands of years and many generations. Our longstanding management of the ecosystems and resources therein transcend the jurisdictional siloes that often constrain and limit federal and provincial environmental governance today. TWN’s assessment speaks from this perspective: a holistic and thorough overview of Burrard Inlet, including the long history of biodiversity and human occupation, and their significance on the community today. The assessment also evaluates something the Crown still does not: the cumulative effects of development over time in Burrard Inlet, and the critical thresholds that in many instances have been exceeded. Tsleil-Waututh, for example, cannot safely harvest and consume shellfish in Burrard Inlet: this threshold was exceeded in 1972. Tsleil-Waututh therefore requires environmental remediation to address this impact; until TWN can once again harvest healthy shellfish in Burrard Inlet, TWN law has been violated.

TWN’s explicit consideration of cumulative effects in 2015 occurred years before the Province of BC would be admonished by the BC Supreme Court in the groundbreaking Yahey case for failing to consider the significant and devastating role cumulative effects have on infringing Indigenous rights and title. As Crown governments consider how to incorporate these elements into their decision-making, TWN’s Assessment provides one potential blueprint.

Once TWN Council reviewed the assessment of TMX, they concluded that the project presented a risk too great to accept. On this basis, TWN withheld our free prior and informed consent. In the time since, despite two consultation processes, Canada has not adequately addressed the concerns, including oil spill risk, inability to effectively recover spilled oil, and impacts to endangered killer whales, to name a few. These concerns are still outstanding, and TWN therefore continues to withhold our free, prior and informed consent.

TMX aside, TWN’s Assessment continues to be an invaluable resource to understand Burrard Inlet, its ecosystems, its people, and its history, and is a powerful primer on who Tsleil-Waututh are, as well as what Indigenous law is, and what an independent assessment can look like using uniquely Coast Salish indicators. (See our Indigenous Legal Orders section, for example.)

Indigenous Law 7 Years on

In 2015, the National Energy Board was preparing to coordinate with other governments that held jurisdiction relevant to the project and the ability to carry out its own environmental assessment. When the Tsleil-Waututh Nation identified itself as a level of government with relevant jurisdiction over this matter, with the ability to carry out its own environmental assessment, and therefore a government whose decision on the project needed to be taken into account, the NEB didn’t know what to do.

We remember fondly the Spring day in 2015 when we released the assessment at Whey-ah-Wichen (Cates Park), an ancestral village site that continues to be an important place to our people. In this important place on the shore of Burrard Inlet, with Trans Mountain’s marine terminal in the background, Tsleil-Waututh leadership launched the Assessment, alongside drummers, dancers, invited dignitaries, and legal experts. At the time, our work was lauded as groundbreaking, “an expression of the nation’s inherent jurisdiction and law.”[1] That day, several legal scholars published this piece in the Georgia Straight which situated the assessment in important context:

The inherent jurisdiction and laws which Tsleil-Waututh relied on in completing its Assessment exist independently of, and pre-date the assertion of sovereignty by Canada. Section 35(1) of the Canadian Constitution recognizes and affirms such existing Aboriginal rights, including Aboriginal title and governance rights.

In the landmark Supreme Court of Canada decision Tsilhqot’in Nation v. British Columbia, Canada’s highest court affirmed that Aboriginal title encompasses a right to “proactively use and manage the land” including making land use decisions. The Tsleil-Waututh Assessment is a pioneering example of a First Nation acting on this authority to review and decide whether a project should proceed in its territory.

TWN submitted our assessment and our resulting informed decision to reject the project as a distinct order of government. The NEB, unprepared for a First Nation to claim this jurisdictional authority, simply subsumed our assessment under their own evidence for consideration in what they ultimately deemed a Crown decision. This stripped away any recognition of TWN’s governance authority, and misrepresented the assessment. Even so, the assessment did not appear to influence the NEB’s decision.

In the time since 2015, the phrase “Indigenous law” has become more common. Indigenous law has become increasingly recognized as a legitimate legal order in a legally pluralistic Canada. There are now law schools in Canada that offer law degrees in both Canadian and Indigenous law (UVic being a pioneering example; McGill is following suit).

Does this mean that Indigenous law, then, is sufficiently applied, recognized and respected by other orders of government? Sadly, for the most part no. We have a long way to go still. There are other powerful examples of instances in which this has occurred—the Stk’emlúpsemc te Secwépemc, for example, conducted a robust and sophisticated impact assessment on the proposed Ajax mine in 2017, which led to the Province of BC rejecting the mine. The Squamish Nation further conducted an assessment on the proposed Woodfibre LNG facility which was ultimately approved by the Squamish Nation. When the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act was overhauled in 2018, giving way to the Impact Assessment Act, Canada included a new provision for Indigenous-led assessments to be considered. Yet we are still in the early days; it remains to be seen how this works in practice, particularly in the event of a repeat of TWN’s experience of TMX: what happens when Canada approves a project, but a First Nation says no?

While Indigenous law is increasingly recognized in the public sphere as a legitimate, contemporary, and applicable body of law, this recognition remains largely rhetorical. The question remains as to how Indigenous law will be applied and adhered to, respected and upheld by other jurisdictions such as the provincial and federal governments. This work is the project ahead of us, and we continue to walk this path alongside the many other First Nations and legal experts working to strengthen the role of Indigenous law and governance.

As we fall deeper into the climate crisis, we all need to find better ways to make decisions that will consider more than the maximization of profit. The revitalization and application of Indigenous law to contemporary issues will be an important part of this change. These laws have allowed us to live with abundance while ensuring a healthy future for generations to come, and we will never stop living by our laws and upholding our sacred responsibility to the land, water air and everything living within our homelands.

[1] https://www.straight.com/news/457891/canadian-law-profs-statement-tsleil-waututh-nation-rejection-kinder-morgan-pipeline