What is Diluted Bitumen and is it More Dangerous than Conventional Oil?

The BC Government has stated that the proposed Trans Mountain Pipeline should not move forward until the potential impacts of a diluted bitumen spill are studied.

The Royal Society of Canada’s 2015 expert panel report identified seven major research gaps regarding scientific uncertainties on bitumen.

The panel identified seven “high priority research needs,” which are:

- The impact of oil spills in high-risk and poorly understood areas, such as the Arctic.

- The effects on aquatic wildlife.

- A national baseline research and monitoring program for areas that may be affected by a spill in the future

- Controlled field research to understand how a spectrum of crude types behave in different ecosystems and conditions

- Investigating the efficacy of spill response and being able to learn from spills soon after they occur.

- Improved spill prevention

- Improved risk assessment protocols for oil spills.

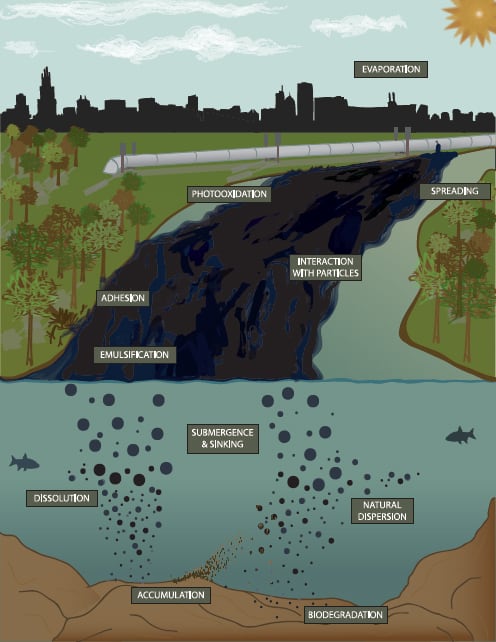

Graphic via the National Academy of Science -Spills of Diluted Bitumen from Pipelines: A Comparative Study of Environmental Fate, Effects, and Response (2016)

The National Academy of Science did a comprehensive study of Diluted Bitumen. The results of this study were presented to the National Energy Board but they did not consider them in their approval of the project. and found

“In comparison to other commonly transported crude oils, many of the chemical and physical properties of diluted bitumen, especially those relevant to environmental impacts, are found to differ substantially from those of the other crude oils. The key differences are in the exceptionally high density, viscosity, and adhesion properties of the bitumen component of the diluted bitumen that dictate environmental behavior as the crude oil is subjected to weathering (a term that refers to physical and chemical changes of spilled oil)…

…For any crude oil spill, lighter, volatile compounds begin to evaporate promptly; in the case of diluted bitumen, a dense, viscous material with a strong tendency to adhere to surfaces begins to form as a residue. For this reason, spills of diluted bitumen pose particular challenges when they reach water bodies. In some cases, the residues can submerge or sink to the bottom of the water body.”

Diluted Bitumen FAQ

Source:

InsideClimate News won the 2013 Pulitzer Prize in national reporting for their series on a dilbit oil spill in the Kalamazoo River. The following is from their primer on understanding dilbit as part of the series.

What is dilbit?

Dilbit stands for diluted bitumen.

Bitumen is a kind of crude oil found in natural oil sands deposits—it’s the heaviest crude oil used today. The oil sands, also known as tar sands, contain a mixture of sand, water, and oily bitumen. The tar sands region of Alberta, Canada is the third largest petroleum reserve in the world.

What makes bitumen different from regular or conventional oil?

Conventional crude oil is a liquid that can be pumped from underground deposits. It is then shipped by pipeline to refineries where it’s processed into gasoline, diesel and other fuels.

Bitumen is too thick to be pumped from the ground or through pipelines. Instead, the heavy tar-like substance must be mined or extracted by injecting steam into the ground. The extracted bitumen has the consistency of peanut butter and requires extra processing before it can be delivered to a refinery.

There are two ways to process the bitumen.

Some tar sands producers use on-site upgrading facilities to turn the bitumen into synthetic crude, which is similar to conventional crude oil. Other producers dilute the bitumen using either conventional light crude or a cocktail of natural gas liquids.

The resulting diluted bitumen, or dilbit, has the consistency of conventional crude and can be pumped through pipelines.

What chemicals are added to dilute the bitumen?

The exact composition of these chemicals, collectively called diluents, is considered a trade secret. The diluents vary depending on the particular type of dilbit being produced. The mixture often includes benzene, a known human carcinogen.

If dilbit has the consistency of regular crude, why did it sink during the Kalamazoo spill?

The dilbit that spilled in (the Kalamzoo River) was composed of 70 percent bitumen and 30 percent diluents. Although the dilbit initially floated on water after pipeline 6B split open, it soon began separating into its different components.

Most of the diluents evaporated into the atmosphere, leaving behind the heavy bitumen, which sank under water.

According to documents released by the National Transportation Safety Board—a federal agency that is investigating the spill—it took nine days for most of the diluents to evaporate or dissolve into the water.

Can conventional crude oil also sink in water?

Yes, but to a much smaller extent.

Every type of crude oil is made up of hundreds of different chemicals, ranging from light, volatile compounds that easily evaporate to heavy compounds that will sink.

The vast majority of the chemicals found in conventional oil are in the middle of the pack—light enough to float but too heavy to gas off into the atmosphere.

Dilbit has very few of these mid-range compounds: instead, the chemicals tend to be either very light (the diluents) or very heavy (the bitumen).

Because bitumen makes up 50 to 70 percent of the composition of dilbit, at least 50 percent of the compounds in dilbit are likely to sink in water, compared with less than 10 percent for most conventional crude oils.

How do you know whether a particular type of crude oil will sink or float?

The industry classifies different crude oils as light, medium or heavy, based on their densities. There is debate over the cutoffs for these categories, but bitumen falls into the “extra heavy” category because it is denser than water. The diluted bitumen that spilled from 6B was lighter than water and considered heavy crude oil.

But density alone doesn’t determine whether a particular type of crude oil will sink or float, said Nancy Kinner, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of New Hampshire who studies submerged oil. Weather and other conditions can change the buoyancy of crude oils: for example, crudes that are lighter than water can sink if they mix with sediment.

That’s exactly what happened with the bitumen from 6B. In general, the density of bitumen ranges from slightly heavier than water to barely lighter than water. The bitumen that spilled in Marshall was at the lighter end of the scale. Marc Huot, a technical and policy analyst at the Pembina Institute’s Oilsands Program, said the bitumen’s density was so close to that of water that it was in “a gray area. It may or may not float depending on [conditions]…think of a log—it floats, but not very well.”

But as the bitumen mixed with grains of sand and other particles in the river, the weight of the sediment pulled the bitumen underwater.

Why has it been so hard to clean up submerged oil in the Kalamazoo?

Existing cleanup procedures and equipment are designed to capture floating oil. Because the Marshall accident was the first major spill of dilbit in U.S. waters, cleanup experts at the scene were unprepared for the challenge of submerged oil.

The EPA has supervised the cleanup of nearly 8,400 spills since 1970, but in multiple interviews with InsideClimate News, agency officials said the Marshall spill cleanup was unlike anything they’d ever faced.

“[It’s] not something a lot of people have dealt with,” said Kinner. “When you can’t see [the oil], you don’t know where it is, so it’s very hard to clean it up.”

Once cleanup crews locate submerged oil, it’s hard to remove it without destroying the riverbed. Cleanup workers in Marshall were forced to improvise less invasive procedures that balanced oil cleanup with protecting the ecosystem.

On July 16, 2010, just nine days before the Marshall accident, the EPA warned that the proprietary nature of the diluents found in dilbit could complicate cleanup efforts. The agency was commenting on the State Department’s Draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) of the Keystone XL, a proposed pipeline that would carry Canadian dilbit across six U.S. states and the critically-important Ogallala aquifer.

“First, we note that in order for the bitumen to be transported by the pipeline, it will be either ‘diluted with cutter stock (the specific composition of which is proprietary information to each shipper) or an upgrading technology is applied to convert the bitumen to synthetic crude oil,'” the EPA wrote. “…Without more information on the chemical characteristics of the diluent or the synthetic crude, it is difficult to determine the fate and transport of any spilled oil in the aquatic environment.

“For example, the chemical nature of diluent may have significant implications for response as it may negatively impact the efficacy of traditional floating oil spill response equipment or response strategies. In addition, the Draft EIS addresses oil in general and as explained earlier, it may not be appropriate to assume this bitumen crude/synthetic crude shares the same characteristics as other oils.”

How does dilbit affect pipeline safety?

Some watchdog groups contend that dilbit is more corrosive than conventional oil and causes more pipeline leaks. The industry disputes that theory, and there are no independent studies to support either side. In late 2011, Congress passed a bill that ordered the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) to study if dilbit increases the risk of spills. Results are expected in 2013.

The industry says that Canadian tar sands oil is very similar to conventional heavy crudes from places such as Venezuela, Mexico and Bakersfield, California. Those crude oils, however, aren’t transported through the nation’s pipelines. The Bakersfield oil is processed at on-site refineries, while the Venezuelan and Mexican imports are shipped via tankers to refineries on the U.S. Gulf Coast.

The same watchdogs that criticize dilbit say that synthetic crude—which is also made from bitumen—poses no additional threats to pipeline safety. The U.S. currently imports more than 1.2 million barrels of Canadian dilbit and synthetic crude per day, and that figure is expected to grow dramatically in next decade. Most of the increased production will come from dilbit—because Canada’s synthetic crude upgraders have reached capacity, and because it’s more financially lucrative for U.S. refineries to process dilbit.

Source:

Is DilBit Worse for Climate Change?

Yes, it is. Read this study from the University of Calgary for more information.

“Researchers from the University of Calgary, Stanford University and the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace compiled information to create what they call the Oil-Climate Index, a database that calculates GHG emissions from oilfield, midstream, refinery and end- user sources. They initially looked at 30 companies, chosen mainly because of availability of information.

The study showed oilsands and other heavy crudes tended to have the highest GHG emissions. But it also found higher emissions result from oil that is produced with more natural gas or water or from very deep or very remote wells. Emissions rose if the companies were allowed to burn off solution gas or if they had to heat formations with steam to pump out the oil.

The study looked at four oilsands products. Suncor’s H blend SCO (synthetic crude oil) had the highest emissions of the four (and of the 30) at more than 800 kilograms of carbon dioxide per barrel. Syncrude SCO was third highest, Suncor A blend was seventh and Cold Lake dilbit (a mix of bitumen and light petroleum diluent to allow it to flow in a pipeline) placed 11th.

Bergerson pointed out the dilbit figures assume the diluent went all the way to the refinery and was used to make transportation fuel. The emissions count would be higher if the diluent was recycled back to the oilsands producer, as is often the case…”

For more information check out CBC Radios Quirks and Quarks – Trans Mountain spill ‘could have significant impacts’ says Canadian government scientist